THE UNIVERSAL BROTHERHOOD

THE DUTY AND PRIVILEGE OF JOY AND JOY-GIVING

Man naturally longs to be happy. If some deliberately turn their backs upon happiness it is either because they are seeking it where it is not to be found or because they are seeking fuller, higher and more enduring joys than those that they forego. If some deliberately seek misery it is as a means or instrument of happiness or of something which is considered to be capable of giving happiness or from which happiness is expected to rise in the future. Man craves happiness because happiness is his normal condition. All consciousness is pleasurable under normal conditions, and under normal conditions all conscious activities are pleasurable in proportion to the dignity of the highest plane on which they are exercised and to the measure in which the whole being participates in them.

The pursuit of happiness is in some way involved in all conscious activities. Insofar as happiness is already possessed the activities are directed towards its perpetuation, increase or diffusion; and insofar as it is absent the activities are directed towards its acquisition. Sometimes it is pursued directly, sometimes indirectly; sometimes for oneself, sometimes for others. Even when it is not acknowledged to be a legitimate object of pursuit it is recognized that the direction of the energies towards right ends gives rise, even though incidentally, to a larger measure of happiness than would result from misdirected efforts. Even when it is not acknowledged to be possible of acquisition it is recognized that all activities should either be directed towards the mitigation of suffering or towards objects the pursuit or acquisition of which is attended or followed by at least a mitigation of suffering. Even when complete indifference to happiness or misery is aimed at, or considered to be the ideal condition, that indifference is looked upon as being calculated to make life more endurable than it would otherwise be. And the mitigation of suffering and the increase of the tolerability or endurability of life are both of the nature of increments of that lowest and most negative form of happiness consisting of freedom from unhappiness.

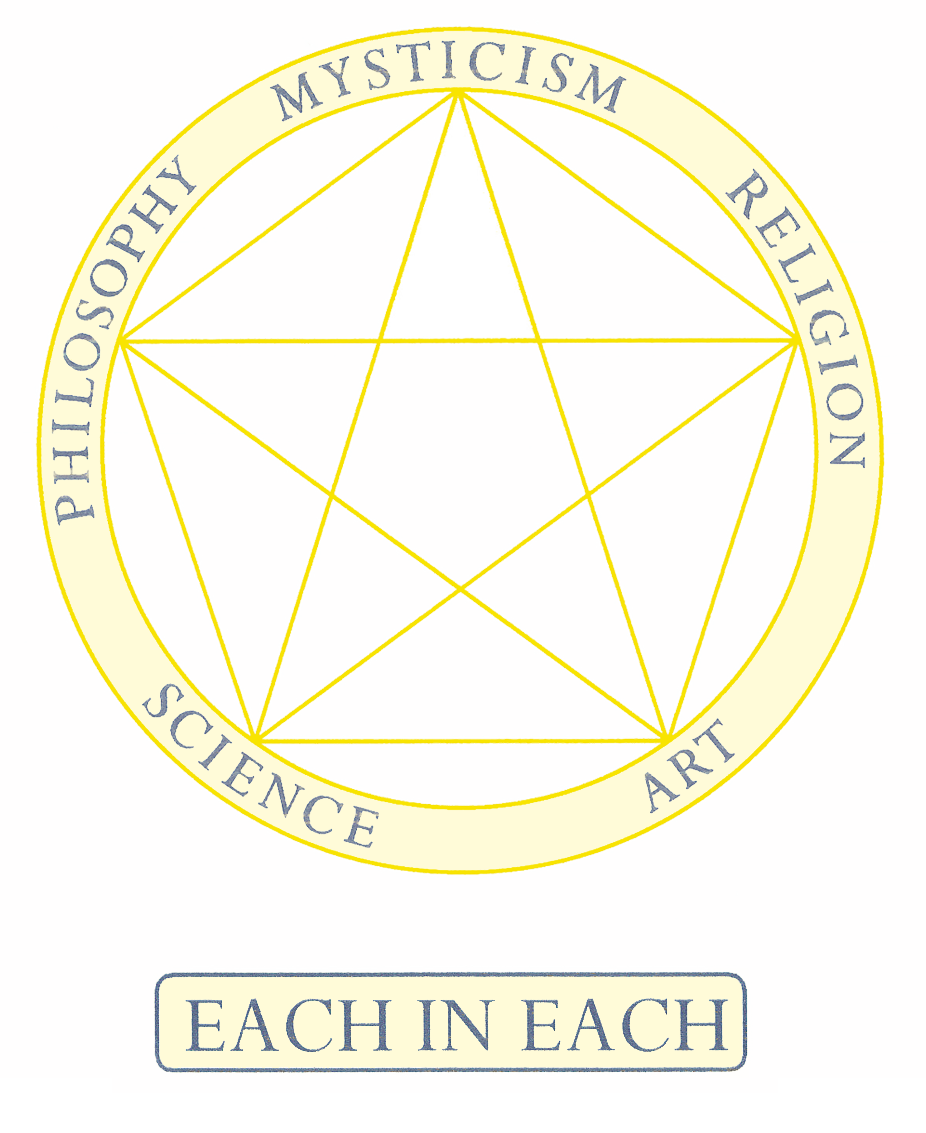

The pursuit of some degree of happiness, either directly or indirectly, either for oneself or for others, has been explicitly recognized by all great religions and philosophies of the world as absolutely obligatory; Buddhism and Schopenhaurism teach, like the Stoicism of antiquity, that the enlightened make the mitigation or annihilation of pain or suffering the foremost object of their endeavors; Hinduism, like Neo-Platonism, teaches man to aspire to union with the One Who is Bliss Itself; Mazdeism and Judaism teach, with the Socratic school, that the supreme end is righteousness the fruit of which is joy; Confucianism and Shintoism teach that the true sage attains to happiness by walking in the Middle Path of perfect social virtue; Epicureanism taught that the true philosopher is he who obtains as much pleasure as possible out of his terrestrial life; Mohammedanism exhausts the powers of human language in describing the felicities, on every plane, by which the perfect practice of Islam in this world is rewarded in the next; and the Sacred Oracles of the Christian religion bid its votaries to “Rejoice always”.

There is no condition of life, and there are no possible circumstances, however disagreeable or painful, in the midst of which many have not succeeded not only in remaining free from interior misery, but also in possessing a large measure of positive happiness and in giving happiness to others. What one person can do, under any given circumstances, can be done by another; and therefore happiness is, under all circumstances, possible of attainment, and the happiness of others can, under all circumstances, be promoted.

All men admit that, in itself considered, and leaving out of consideration its causes, effects and results and the conditions under which it is experienced, pleasure is better than pain, happiness better than misery, joy better than sorrow. Even those who most insist upon the strengthening, up-lifting, ameliorating, purifying and progress-promoting effects of pain, misery and sorrow admit that it is the duty of all men to so act as to increase the happiness of others, either in the present or the future, and even though at the cost of present pain. But if it is a duty to promote the happiness of others, it must necessarily be a duty likewise to act in such a manner as will promote one’s own happiness; therefore, it cannot be a duty to do evil either to others or to oneself, and if the happiness of others should be promoted, it must be a good and that good should be sought for oneself as well, although without detriment to any other goods for which it is one’s more imperative or more immediate duty to seek.

The acquisition of happiness for oneself tends to promote the happiness of others; for he who is happy radiates happiness, creates it in others by unconscious suggestion and inspires others to acquire it by imitation. Under the influence of happiness the heart and purse-strings open, a spirit of helpfulness spontaneously arises, the countenance is irradiated and the very tones of the voice become a benison. Few lives are so deeply in misery as not to be open to the blessed contagion of a smile.

The giving of happiness to others tends to increase one’s own, both by a sense of complacency in a good deed, by the natural reaction upon oneself of the happiness produced in others, and by inspiring in others a gratitude that will naturally express itself in corresponding favors, benefits or services.

The increase of the sum total of happiness in any portion of the human race correspondingly brightens and beautifies its life, facilitates its labors and results in a corresponding increase of harmony, productivity and efficiency.

Since it is the duty of every man to labor for the highest good of himself, of others and of the human race, at least as represented in some one of its subdivisions, it is his duty to be happy, to produce happiness and to bring about conditions favorable to happiness. He who is not happy himself cannot do his full share in making others happy; he who is not adding to the aggregate happiness of the race is neither giving nor receiving the due measure of joy.

From the lack of happiness all other ills follow. Happiness leads to happiness and invites all that conduces to happiness while misery invokes further misery and makes conditions still more misery-breeding

Joy is fertile; misery is sterile.

Joy is illuminating; misery is beclouding.

Joy is invigorating; misery is debilitating.

Joy is enriching; misery is impoverishing.

Joy is beautifying; misery is deforming.

Joy is love-engendering; misery is hate-arousing.

Joy is enlarging, broadening and deepening; misery is contracting, narrowing and superficialzing.

The pain that is really purifying and the sorrow that is really uplifting are never unmixed with joy; they are in reality revelations of the essential happiness since they show that it can endure even under the most untoward conditions, over-arching in the firmament of the spirit all the turmoil of the lower levels like the rainbow above the storm.

The treasure of happiness is not to be lightly attained to. Perfect happiness is enduring; for a merely transitory happiness is overshadowed by the horror of the end, and evanescent pleasures are often purchased by greater pains. Perfect happiness is all-inclusive; delight on one plane is only a spark of joy when on other planes there is deadness or misery. Perfect happiness is revelatory; for the joy which does not spring from the deep and inexhaustible fountains of life is only a mirage behind which lies the sands of the desert. Whenever any element of the inner or outer life is not what it should be the defect is manifested in consciousness by a corresponding taint of misery; or, if, by some intoxication, there is a semblance of perfect happiness there will come a moment of sobriety in which the flaws that mar it will become apparent. While an illusory pleasure or contentment is often purchased by ignorance or forgetfulness, it still more frequently happens that through ignorance or non-use of knowledge men fail, not only to find out the means to perfect happiness, but even to make that type of life which they are actually leading yield its full mead of delight, either real or illusory. There is no human existence, no matter under what conditions, that cannot be made thrillingly intense, sublimely significant and useful and a means of happiness to oneself and others. True happiness is within the reach of all who will rightly use the means to it that no one are lacking. But the possession of true knowledge, true wisdom, legitimate power, or honorable opportunity of whatsoever kind, makes possible a happiness that is proportionately higher in quality or greater in volume.

To be able to attain to the very highest happiness and the greatest possible power of producing happiness it is necessary to fully know and understand, or to be guided by those who fully know and understand the true system of the universe; for happiness arises in proportion as the whole inner and outer life and the totality on one’s relationships are perfectly adjusted to all the details of Reality or at least brought fully into conformity with the great underlying laws.

—–

The reader who sincerely desires to attain to the fullest possible degree of present and future happiness or to be enabled to contribute as much as possible to the happiness of his fellowmen, and who is willing to learn and do whatever seems necessary for these ends, is invited to communicate further with the one from whom they received this paper, stating that they have read it with interest. Or, if they do not know how to reach them, they may write to the person whose address is herewith given. If they have not already read the Open Instructions on Aspiration and Attainment and the Necessity of Right Knowledge they should ask to be supplied with them.

——-